‘Equus’ // Ad Astra

‘Equus’ was primal.

Setting pulses racing with their latest production, Ad Astra has presented the psychological thriller, ‘Equus’, in a brave interpretation. The play, which epically twists down a path filled with macabre motifs, is a daring choice for any theatre group wanting to leave their mark.

When first performed in 1973, ‘Equus’ was deemed a shocking controversy due to its graphic depictions and violent finale. Connections within the text were made to pagan religions, extreme spiritual rituals and sexual desires. At its time of conception, its cruelty and wild reverence made it an explosive spectacle. Nowadays, the same rings true, only the play’s notoriety is more affiliated with Harry Potter, horses and a lead actor baring all.

Written by Peter Shaffer, ‘Equus’ rides the mystery in discovering what drove of a boy, Alan Strang, to blind some horses with a metal spike. For Alan, his world is populated by bizarre dreams and the idea that horses are divine creatures where he can escape his current existence. His weary psychiatrist, Martin Dysart, attempts to explore the kid’s inner torments, delving into his parental background and his fascination with the animal. While trying to get to the bottom of the incident at hand, Dysart begins to admire Alan’s capacity for worship, all while becoming exhausted by his temperamentality.

Ad Astra, along with a dedicated team of creatives, has approached this text cautiously and handled its disturbing themes with emotional sensitivity. Gone is the shock value that most other productions navigate towards, replaced with a delicate retelling of one mans primal theology in an oppressed world. The team opted for a conservative presentation, with stylised direction and clean transitions. There was no nudity, no sexually aggressive content and actors sustained an innocence in their portrayals. Although this wasn’t a focus for Ad Astra’s production, the choice in removing nudity (especially in an extremely enclosed space) was the right option. It allowed the actors to breathe life into the text, without pulling focus from the dark themes.

The staging was set in the round, with limited design aesthetics and skeleton-like set pieces. Only three benches were used for the entire performance; morphing into bedrooms, psychiatrist offices, home lounges, horse stables and so forth. While scenes were crafted with a minimalist nature, they relied heavily on the imagination of audience members to transport them within the story. Lighting Design by B’Elanna Hill was the only addition that helped the audience navigate the various places and time. A clever, and cost-effective’ concept, this staging style obviously intended to focus on an actor’s performance in a no-frills approach.

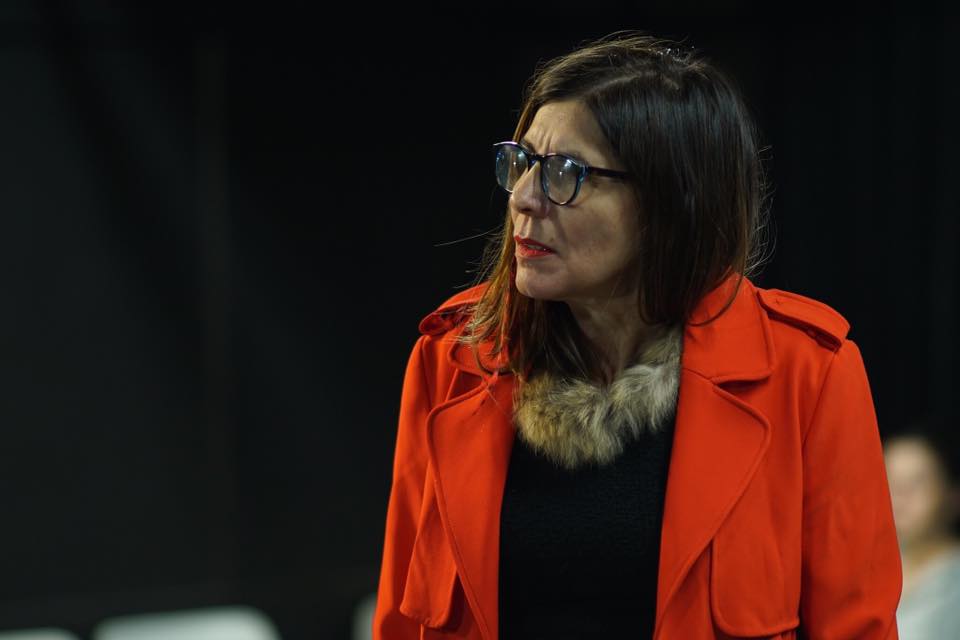

Ticking the dramatic piece off her theatrical bucket list, director, Jacqueline Kerr, utilised a percussive, choreographed tone to her direction with mechanical transitions. While the ‘in-the-round’ concept proved innovative in the tight theatre space, the raw presentation of the storyline meant that the audience impact was sometimes lacking. As actors moved around on the raised, boxed staging, they would sit in corners or turn a certain way, which blocked sightlines for patrons caught behind them. This presented a challenging feat for emotional connection, especially when actors presented plot points away from a clear viewing – the audience couldn’t see their reactions and that took us out of the world when we couldn’t engage effectively.

This blocking aspect, along with limited sound effects, also affected the tension. Basic styling made the play sit lightly in the room. For example, the word-heavy dialogue was delivered in one spot for a lengthy period of time; drawing out the action and masking the drive of scenes. Without the assistance of technical elements, it was difficult to become fully invested. Consequently, some scenes felt clinical rather than with the high-stakes nature of the script.

Attention was clearly paid to scenes in the stables where ensemble members embodied horses, and Alan’s obsession with the animal became clear. It was evident Kerr had specific imagery in mind for these moments. As these plot points heightened, the use of strobe lighting and an ambient tribal soundscape really aided the graphic content. It was like the technical components, directed by Danielle Park, came to life at these times and the audience felt the intensity that the show requires. A building of this type of sound at the start of the production and throughout scenes would have carried the tension during the course of the show. At the beginning of the presentation, the audience was left in a blackout for a long while, before an actor walked on stage and the lights came up. In these situations, the sound could have really evoked the drama and created an atmospheric intrigue.

It is worth mentioning that the actors who embraced the challenging task of “playing horses” did so with the utmost dedication. This ensemble – including Eleanora Ginaldi, Peter Cattach, Shea Smith, Felicity O’Leary and director, Jacqueline Kerr – donned steel-framed horse masks that were beautifully crafted, and personified the creatures with believable ‘neighing’ sounds, stamping feet and a physical fluidity in their shoulders and stance.

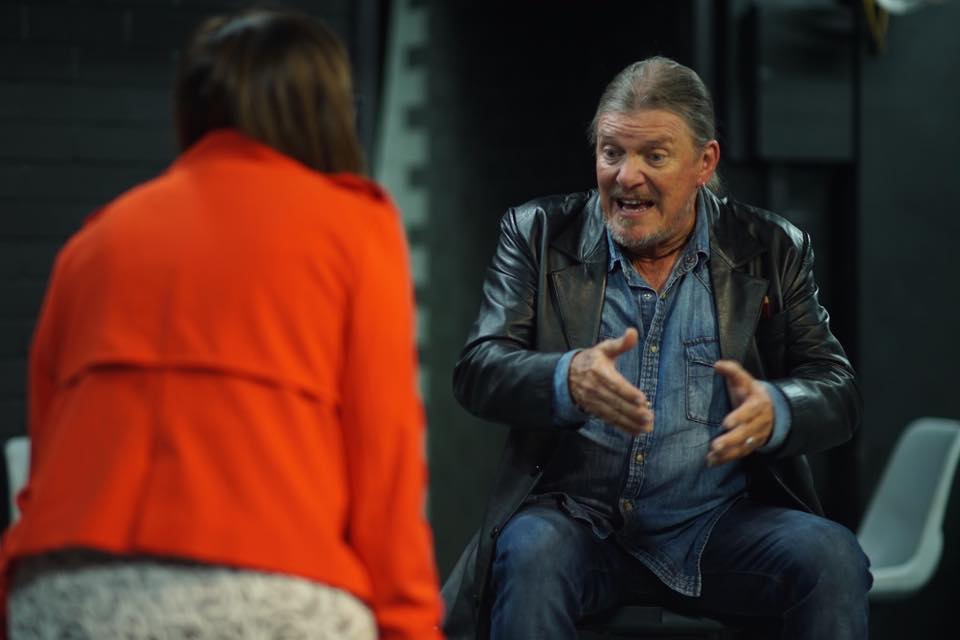

As the troubled teen, Alan Strang, Angus Thorburn was believable and sensual. He delivered lines with a naturalness that oozed inner torment and confusion. Thorburn was also erratic and wild-eyed as he tried to cover his secrets, and shut others out of his world. Richard John Murphy played Martin Dysart with conviction and carried the storyline well, although, his temperament escalated from calm to irate extremely quickly at times. Together with Thorburn, there was a nice chemistry between the two as they learned to trust one another in the boundaries of a psychiatrist and patient relationship.

Other interesting performances came from Michelle Carey as Alan’s mother who was a religious woman with an undeniable love for her son, Claire Erueti as the seductive and likeable stable worker, Jill, and Shea Smith who portrayed a range of different characters with versatility, strong physicality and wholesome charm.

‘Equus’ deals with some very dark and confronting subject matter. Although the pace was a slow trot at times, Ad Astra has ambitiously chosen a text that challenges its audiences and imprints in their conscious. It’s evident the company are risk-takers, and their trajectory will be leaps and bounds within in our theatrical community.

‘Equus’ performs until Saturday, 20 July 2019, at Ad Astra, Fortitude Valley. For tickets, visit www.adastracreativity.com.